Evidence of Vitrified Stonework in the Inca Vestiges of Peru.

By Jan Peter de Jong & Christopher Jordan

INTRODUCTION

Vitrified stones are simply stones that have been melted to a point where they form a glass or glaze. There is much debate in archaeological circles over the ancient examples under study for two reasons. Firstly, few cases are known to have been tested and even if they have been, there are many questions over how they were made. Glassy rocks form naturally under conditions of high temperature and pressures found in and around volcanoes. Glass or glazes are traditionally created using a furnace. Furnace or kiln examples are found on everyday objects such as glassware and ceramics. Ceramic glazes are created by pasting certain finely crushed stones, sometimes with tinctures, onto fired pots and plates. The whole is then fired to temperatures usually in excess of 1000 degrees centigrade. Many of the ancient vitrified examples are found on objects so large that they cannot be placed in a furnace. Previous analysis concluded that the temperatures needed to produce the vitrification were up to 1,100°C. There are confirmed cases from Scotland, Ireland, France and Germany.

These are mostly forts and buildings with vitrified ramparts. This fusion is often uneven throughout the various forts and even on a single wall. Some stones are only partially melted, whilst in others their adjoining edges are fused firmly together. In many instances, pieces of rock are enveloped in a glassy enamel-like coating, which binds them into a whole. At times, the entire length of the wall presents one solid mass of vitreous substance.

There are many more examples from Malta, Egypt, Iraq, Sudan, South East Asia and others that are speculated to fall into the grouping. However, these have not all been subjected to scientific testing like the European cases. They simply appear to be glazed finishes on equally large objects or on walls that are impossible to fire conventionally.

There has been much discussion about the Inca vestiges in the Peruvian Andes. It mostly revolves around whether the stones are vitrified or not. This article focuses on these Peruvian cases where there are indications of heat treatment.

There are many more examples from Malta, Egypt, Iraq, Sudan, South East Asia and others that are speculated to fall into the grouping. However, these have not all been subjected to scientific testing like the European cases. They simply appear to be glazed finishes on equally large objects or on walls that are impossible to fire conventionally.

There has been much discussion about the Inca vestiges in the Peruvian Andes. It mostly revolves around whether the stones are vitrified or not. This article focuses on these Peruvian cases where there are indications of heat treatment.

THE PERUVIAN CASE STUDY

The vitrified examples under study come from famous Peruvian sites, in South America. Without testing, the debate is open to claims of unusual polishing techniques, natural degradation, lava flows and many other odd explanations. The analysis below eliminates some of these ideas.

The vitrified stones of Peru were first brought to popular attention by Erich von Daniken in the 1970s. He noted the vitrification at Sacsayhuaman in his book Chariots of the Gods. Peruvian Alfredo Gamarra had identified this vitrification earlier. The identification and cataloging of these intriguing stones has been carried on by Alfredo’s son Jesus Gamara, and Jan Peter de Jong.

The vitrified stones of Peru were first brought to popular attention by Erich von Daniken in the 1970s. He noted the vitrification at Sacsayhuaman in his book Chariots of the Gods. Peruvian Alfredo Gamarra had identified this vitrification earlier. The identification and cataloging of these intriguing stones has been carried on by Alfredo’s son Jesus Gamara, and Jan Peter de Jong.

In Sacsayhuaman, there are many other indications of the use of heat. Strange marks on the stones like the one pictured can be found; shiny, completely smooth and with another color to the rest of the rock:

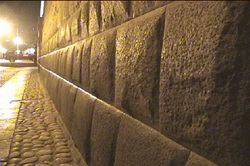

Vitrification appears on different kinds of stones and structures, as the photos show. It is found on the perfectly fitted walls with irregular blocks. It is also observed on walls made with regular oblong blocks. It has been spotted on mountainsides, caves and rocks in situ. The location arrangements vary as well. Some sites are surrounded or overbuilt by walls whilst others have single exposed isolated stones. There seems to have been some very adaptable ancient technology at work.

A list of vestiges where stonework seems to have been treated with this technology include; In Cusco, the walls of Koricancha, Loreto Street, Sacsayhuaman, Kenko, Tetecaca, Templo de la Luna (or Amaru Machay), Zona X, Tambo Machay, Puca Pucara, Pisac, Ollantaytambo, Chinchero, Machu Picchu, Raqchi and in Bolivia in Tiahuanaco.

Vitrification appears on different kinds of stones and structures, as the photos show. It is found on the perfectly fitted walls with irregular blocks. It is also observed on walls made with regular oblong blocks. It has been spotted on mountainsides, caves and rocks in situ. The location arrangements vary as well. Some sites are surrounded or overbuilt by walls whilst others have single exposed isolated stones. There seems to have been some very adaptable ancient technology at work.

A list of vestiges where stonework seems to have been treated with this technology include; In Cusco, the walls of Koricancha, Loreto Street, Sacsayhuaman, Kenko, Tetecaca, Templo de la Luna (or Amaru Machay), Zona X, Tambo Machay, Puca Pucara, Pisac, Ollantaytambo, Chinchero, Machu Picchu, Raqchi and in Bolivia in Tiahuanaco.

Archaeologists assume that the perfect fitting stones are the most developed style of the Incas. Regardless, there is no explanation of the shiny surfaces that can be observed. These often appear on the borders where the stones join perfectly. It is normally assumed that these parts were simply polished by the Incas.

During many visits to the vestiges mentioned, Jesus Gamarra and Jan Peter de Jong have examined these stones with highly reflective surfaces. They have captured many of them on video. Through personal observations and analysis of the video material, they have concluded that something other than polishing has occurred.

During many visits to the vestiges mentioned, Jesus Gamarra and Jan Peter de Jong have examined these stones with highly reflective surfaces. They have captured many of them on video. Through personal observations and analysis of the video material, they have concluded that something other than polishing has occurred.

IDENTIFYING VITRIFIED STONES

Many cases display some or all of the qualities mentioned below. The vitrified spots show discoloration and smoothness around the particular areas. They clearly look like the stone has been melted just in those spots. A simple flashlight test was developed, to help identify the layers of glaze or glass.

Filming was carried out at night with a flashlight beam passing through the glaze. This shows the reflection and diffraction of the light as it passes through the surface. Sacsayhuaman, Kenko and Loreto Street were all filmed at night using a flashlight or the nocturnal illumination to capture the effect.

The following traits help to identify vitrified stones:

The melted effect is obvious

Reflection is high

The layer refracts, diffracts and diffuses light

A separate vitrified layer is present on the surface

Damaged layers show a ´film´ on the stone

The glazed layer is independent of rock type

The surface is smooth to the touch even if the surface is irregular

There is often associated heat discoloration surrounding the glaze

Filming was carried out at night with a flashlight beam passing through the glaze. This shows the reflection and diffraction of the light as it passes through the surface. Sacsayhuaman, Kenko and Loreto Street were all filmed at night using a flashlight or the nocturnal illumination to capture the effect.

The following traits help to identify vitrified stones:

The melted effect is obvious

Reflection is high

The layer refracts, diffracts and diffuses light

A separate vitrified layer is present on the surface

Damaged layers show a ´film´ on the stone

The glazed layer is independent of rock type

The surface is smooth to the touch even if the surface is irregular

There is often associated heat discoloration surrounding the glaze

|

|

|

The refraction effect can be seen in the video of ‘the Inca Throne’ at Sacsayhuaman. The rainbow effect is clearly captured by the camera. This is directly linked to the light passing through the glass layer and splitting into its constituent parts. After noticing this effect, it was also detected on videos of other vitrified stones. This can be viewed on this short video: Inca throne Refraction effect, and on the DVD that will be available shortly.

The DVD ”The Cosmogony of the 3 Worlds” shows an overview of this phenomenon in the chapter on Vitrified Stones. This is available on youtube.

The DVD ”The Cosmogony of the 3 Worlds” shows an overview of this phenomenon in the chapter on Vitrified Stones. This is available on youtube.

VITRIFIED STONE SAMPLE ANALYSIS

A small sample from the Peruvian site called Tetecaca was collected and then analyzed by the University of Utrecht, Holland. The sample is from a rock outcrop above Cuzco. Inside the cave there is an altar formed from rectangular shapes made of the rock. Several lines in the rock have a shiny surface, as if they were branded into the rock. They are on right lines on the wall of the cave. The walls are cut out with curved and rectangular forms in them. These are man made structures, which rules out natural phenomena. The photos show the site.

Pictures from inside of the cave, walls with long, straight reflecting lines and an altar structure:

Pictures from inside of the cave, walls with long, straight reflecting lines and an altar structure:

RESULTS & CONCLUSION

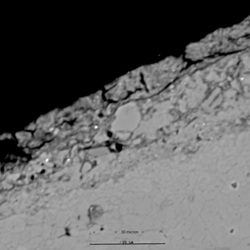

Microscope Photos

The microscope photograph of the sample shows two distinct regions, the surface layer and the body stone. There is a less distinct intermediate area between the two that seems to transition from stone body to surface layer. Samples from all three regions were subjected to detailed analysis.

Photo 1: The Vitrified Surface of the Stone

(The line at bottom is 21 micrometer)

The microscope photograph of the sample shows two distinct regions, the surface layer and the body stone. There is a less distinct intermediate area between the two that seems to transition from stone body to surface layer. Samples from all three regions were subjected to detailed analysis.

Photo 1: The Vitrified Surface of the Stone

(The line at bottom is 21 micrometer)

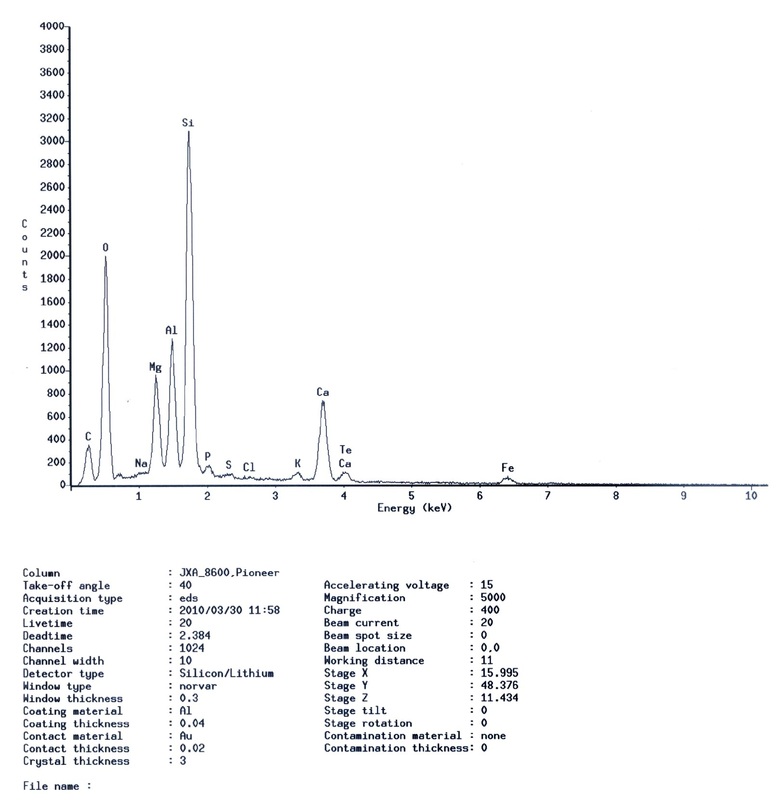

Spectral analysis

Composition of the Surface Layer

Composition of the Surface Layer

Spectral Analysis of Surface Layer

Note: The full set of photos, spectra, tables and text can be found in the full article

Note: The full set of photos, spectra, tables and text can be found in the full article

The body of the stone is limestone, which is not surprising. However, The Vitrified Surface of the stone shows a different spectrum of elements. (See spectra above) The glaring difference is that Silicon is present with much higher concentrations. The trace elements of Aluminum and Magnesium are also significantly higher than the body. Oxygen is also present in double the quantities. The Calcium and Carbon are much lower than the body sample.

The intermediate regions show a gradation between the surface and body of the stone. This implies either the surface layer was somehow ground and mixed with the stone body. The body limestone somehow merged/melted with the surface layer. Alternatively, the limestone constituents could have been a part of the added surface layer.

The surface shows some similarity to Wollastonite, which forms when impure limestone is subjected to high temperatures and pressures. However, the impurities in the surface are not present in the stone body. This indicates that the compounds in the surface layer were added. It appears they were applied and then treated with heat. This option does have some merits, but it is moving towards the techniques of the ceramist.

Whilst the spectra do not show explicitly that the surface is vitrified, the layer does have the composition, sheen, hardness and glassy texture of a glaze. It is very likely that the glaze was made from a ceramic paste applied to the limestone surface. This is reinforced with a comparison to ancient glazed ceramic pottery shards. If an antique ceramic is compared to the spectra of the glaze above there is little to separate the two. In the Paper X-Ray Techniques Applied to Surface Paintings of Ceramic Pottery Pieces From Aguada Culture (Catamarca, Argentina) there are several comparable results. Ignoring the gold leaf and colorants, the key constituents Silicon, Aluminum, Magnesium, Carbon and Oxygen are present in the same ratios.

The glazed results strongly indicate that heat was used to produce the finish. This raises several questions. Even if a layer of a ceramic paste was applied, how was it heated to the requisite temperatures without cracking the limestone? How was the heat produced to treat these structures? Whilst this sample is from a cave, there are similar structures that are outside with the same kind of glaze. The same conclusion may not necessarily be applied to these other cases.

Analysis is needed, but the similarities with the investigated sample and other photographed cases, are clear. It is likely that these other cases are also vitrified. The amount of heat needed to fire the huge stones on which these glazes are found is enormous. In furnaces, the whole body has to be raised to the temperature of the surface glaze.

The intermediate regions show a gradation between the surface and body of the stone. This implies either the surface layer was somehow ground and mixed with the stone body. The body limestone somehow merged/melted with the surface layer. Alternatively, the limestone constituents could have been a part of the added surface layer.

The surface shows some similarity to Wollastonite, which forms when impure limestone is subjected to high temperatures and pressures. However, the impurities in the surface are not present in the stone body. This indicates that the compounds in the surface layer were added. It appears they were applied and then treated with heat. This option does have some merits, but it is moving towards the techniques of the ceramist.

Whilst the spectra do not show explicitly that the surface is vitrified, the layer does have the composition, sheen, hardness and glassy texture of a glaze. It is very likely that the glaze was made from a ceramic paste applied to the limestone surface. This is reinforced with a comparison to ancient glazed ceramic pottery shards. If an antique ceramic is compared to the spectra of the glaze above there is little to separate the two. In the Paper X-Ray Techniques Applied to Surface Paintings of Ceramic Pottery Pieces From Aguada Culture (Catamarca, Argentina) there are several comparable results. Ignoring the gold leaf and colorants, the key constituents Silicon, Aluminum, Magnesium, Carbon and Oxygen are present in the same ratios.

The glazed results strongly indicate that heat was used to produce the finish. This raises several questions. Even if a layer of a ceramic paste was applied, how was it heated to the requisite temperatures without cracking the limestone? How was the heat produced to treat these structures? Whilst this sample is from a cave, there are similar structures that are outside with the same kind of glaze. The same conclusion may not necessarily be applied to these other cases.

Analysis is needed, but the similarities with the investigated sample and other photographed cases, are clear. It is likely that these other cases are also vitrified. The amount of heat needed to fire the huge stones on which these glazes are found is enormous. In furnaces, the whole body has to be raised to the temperature of the surface glaze.

DISCUSSION

The stones pictured above provoke much debate. Explanations on how they were produced vary from the use of advanced machines, simple metal/stone tools, molded stonework, concentrated sunlight and fire methods. Whilst the analysis above says little about the way the shapes were made, it does eliminate some ideas on the means of producing these exquisite finishes.

Heat is used to form glazes. How the heat was applied is not clear. To create ceramics on this scale, the heat production would have been greater than the normal ceramic methods.

Protzen has looked at these effects and suggested it could be achieved with polishing. To date, only Andesite has been attempted with very limited success. After the analysis of the surface layer above, it is clear that polishing alone will not produce the heat needed to produce a ceramic glaze. This eliminates polishing as a means of creation.

Peruvian Alfredo Gamarra has identified vitrification on many stones and has argued that the ancients had a technology to treat stone with heat and that the stone was soft at the moment of construction. The comparison at the spectrum level with clay and ceramic pastes is interesting. Ceramic pastes and clay are soft prior to being treated with heat.

Conventional geological understanding is not compatible with this idea. However, the impression from the vitrified stonework is that the stone was once soft. In many of the stones, there are places where it looks as if objects or molds were pressed into the stone. The perfect fitting stones in the walls of Cusco and the other Inca vestiges could have been obtained more easily this way.

Another option is the use of sun dishes and concentrated sunlight by the ancients. This is discussed by Prof. Watkins in his 1990 paper on fine Inca stonework. In this seminal paper, his chief concern was the methods of cutting the stone. Since he was proposing intense heat to cut the stones, it was not a great step to consider the stones melted. His conclusions have been much maligned since there had been no analyses performed.

The analysis does support this, but the location of the sample was on a wall in a cave. The ceramic paste had to be heated whilst on the stone vestige. This means light would have to be reflected deep into the cave. Whilst it is possible that the ancients were capable of producing flat mirrors for the task, it does seem complicated. This method could work for stones on the surface, but is clearly limited in this case.

If the stones were fired in a kiln, the glaze could be a result of the extremely high temperatures. The knowledge of ceramics in ancient Peru suggests this is a distinct possibility. This prospect however, only arises with the stones that can be placed in a kiln or stonework that is part of a kiln. The examples laid onto the sides of huge natural rocks cannot have been produced by standard fire techniques. As European studies of vitrified forts and experimental work have shown.

There is the possibility is that the cave itself was a kiln. Pots or vases may have been fired in the cave and the ceramic pastes may have been applied to protect the stone structure. There is much discoloration within the cave and innumerable glazed areas. The comparison to vitrified vestiges in the open air or in places without a smoke escape, leaves many questions.

On balance, it has to be admitted that a method is difficult to define. Further analysis of samples from the other sites needs to be undertaken to confirm the use of heat in all of the sites. However, the sample tested shows that the similarity to ceramic pastes is near certain. It is easy to conclude that heat was used. The treatment method may have been similar to the technology used for ceramic pastes, but on a much larger scale.

Heat is used to form glazes. How the heat was applied is not clear. To create ceramics on this scale, the heat production would have been greater than the normal ceramic methods.

Protzen has looked at these effects and suggested it could be achieved with polishing. To date, only Andesite has been attempted with very limited success. After the analysis of the surface layer above, it is clear that polishing alone will not produce the heat needed to produce a ceramic glaze. This eliminates polishing as a means of creation.

Peruvian Alfredo Gamarra has identified vitrification on many stones and has argued that the ancients had a technology to treat stone with heat and that the stone was soft at the moment of construction. The comparison at the spectrum level with clay and ceramic pastes is interesting. Ceramic pastes and clay are soft prior to being treated with heat.

Conventional geological understanding is not compatible with this idea. However, the impression from the vitrified stonework is that the stone was once soft. In many of the stones, there are places where it looks as if objects or molds were pressed into the stone. The perfect fitting stones in the walls of Cusco and the other Inca vestiges could have been obtained more easily this way.

Another option is the use of sun dishes and concentrated sunlight by the ancients. This is discussed by Prof. Watkins in his 1990 paper on fine Inca stonework. In this seminal paper, his chief concern was the methods of cutting the stone. Since he was proposing intense heat to cut the stones, it was not a great step to consider the stones melted. His conclusions have been much maligned since there had been no analyses performed.

The analysis does support this, but the location of the sample was on a wall in a cave. The ceramic paste had to be heated whilst on the stone vestige. This means light would have to be reflected deep into the cave. Whilst it is possible that the ancients were capable of producing flat mirrors for the task, it does seem complicated. This method could work for stones on the surface, but is clearly limited in this case.

If the stones were fired in a kiln, the glaze could be a result of the extremely high temperatures. The knowledge of ceramics in ancient Peru suggests this is a distinct possibility. This prospect however, only arises with the stones that can be placed in a kiln or stonework that is part of a kiln. The examples laid onto the sides of huge natural rocks cannot have been produced by standard fire techniques. As European studies of vitrified forts and experimental work have shown.

There is the possibility is that the cave itself was a kiln. Pots or vases may have been fired in the cave and the ceramic pastes may have been applied to protect the stone structure. There is much discoloration within the cave and innumerable glazed areas. The comparison to vitrified vestiges in the open air or in places without a smoke escape, leaves many questions.

On balance, it has to be admitted that a method is difficult to define. Further analysis of samples from the other sites needs to be undertaken to confirm the use of heat in all of the sites. However, the sample tested shows that the similarity to ceramic pastes is near certain. It is easy to conclude that heat was used. The treatment method may have been similar to the technology used for ceramic pastes, but on a much larger scale.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

-Jesús Gamarra Farfan especially, for showing, explaining and filming these stones.

The following persons we want to thank for their cooperation and feedback:

-Prof. Schuiling, Tilly Bouten and Anita van Leeuwen, Geology department University of Utrecht.

-prof. Kars, Institute for Geo and Bioarchaeology, IGBA, Faculty of Earth and Life Sciences, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam

-David Campbell, www.anarchaeology.com

-Paul D. Burley, www.pauldburley.com

The following persons we want to thank for their cooperation and feedback:

-Prof. Schuiling, Tilly Bouten and Anita van Leeuwen, Geology department University of Utrecht.

-prof. Kars, Institute for Geo and Bioarchaeology, IGBA, Faculty of Earth and Life Sciences, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam

-David Campbell, www.anarchaeology.com

-Paul D. Burley, www.pauldburley.com

REFERENCES

-Jordan, C., The Ancient Solar Premise, Smashword edition, 2011, secretsofthesunsects.wordpress.com

-Gamarra Farfán, J.B., Parawayso. April 2008.

-de Jong, Jan Peter, www.ancient-mysteries-explained.com, www.janpeterdejong.com

-Morris, M., The great pyramid secret, Scribal arts 2010.

-Protzen, J.-P. l986. Inca stonemasonry. Scientific Amer. 254: 94-105.

-Prof. Watkins, I. 1990. How Did the Incas Create Such Beautiful Stonemasonry?” in “Rocks and Minerals” Vol. 65 Nov/Dec 1990.

-Thurlings, B, Wie hielp de mens? Uitgeverij Aspekt. 2008.

-X – Ray spectra of minerals and materials: www.cannonmicroprobe.com/XRay_%20Spectra.htm.

-Silvano R. Bertolino, Victor Galván Josa, Alejo C. Carreras, Andrés Laguens, Guillermo de la Fuente and José A. Riveros in Wiley Interscience Online, Dec. 2008. X-Ray Techniques Applied to Surface Paintings of Ceramic Pottery Pieces From Aguada Culture (Catamarca, Argentina).

Other Links:

Jan Peter de Jong; website Ancient Mysteries Explained, documentaries The Cosmogony of the Three World and Etemenanki, The Tower of Babel in Cusco, Peru?

Christopher Jordan; website Secrets of the Sun Sects, Books "The Ancient Solar Premise" and "The Secrets of the Sun Sects".

-Gamarra Farfán, J.B., Parawayso. April 2008.

-de Jong, Jan Peter, www.ancient-mysteries-explained.com, www.janpeterdejong.com

-Morris, M., The great pyramid secret, Scribal arts 2010.

-Protzen, J.-P. l986. Inca stonemasonry. Scientific Amer. 254: 94-105.

-Prof. Watkins, I. 1990. How Did the Incas Create Such Beautiful Stonemasonry?” in “Rocks and Minerals” Vol. 65 Nov/Dec 1990.

-Thurlings, B, Wie hielp de mens? Uitgeverij Aspekt. 2008.

-X – Ray spectra of minerals and materials: www.cannonmicroprobe.com/XRay_%20Spectra.htm.

-Silvano R. Bertolino, Victor Galván Josa, Alejo C. Carreras, Andrés Laguens, Guillermo de la Fuente and José A. Riveros in Wiley Interscience Online, Dec. 2008. X-Ray Techniques Applied to Surface Paintings of Ceramic Pottery Pieces From Aguada Culture (Catamarca, Argentina).

Other Links:

Jan Peter de Jong; website Ancient Mysteries Explained, documentaries The Cosmogony of the Three World and Etemenanki, The Tower of Babel in Cusco, Peru?

Christopher Jordan; website Secrets of the Sun Sects, Books "The Ancient Solar Premise" and "The Secrets of the Sun Sects".